There is a mantra in the fund-raising world: big donors like to support big ideas. And ideas do not come much larger than at CERN, Europe’s particle-physics laboratory near Geneva in Switzerland. Now the organization — which uses its particle smasher to probe the fundamental structure of the Universe — has registered a charitable foundation to raise funds for its educational, technology-transfer and arts activities.

CERN is not the only big institution to go after donations to fund projects that fall outside the core research remit. The trend is on the rise among large European research organizations. The European Molecular Biology Laboratory (EMBL) in Heidelberg, Germany, is shifting its fund-raising focus from industry sponsorship to private donations. And ITER, the international nuclear-fusion experiment being built in Cadarache, France, is devising a way to deal with the offers of donations that it already receives. What nobody yet knows is the fruit these efforts will bear — whether individuals really want to donate heftily to scientific charities that are not focused on medical solutions.

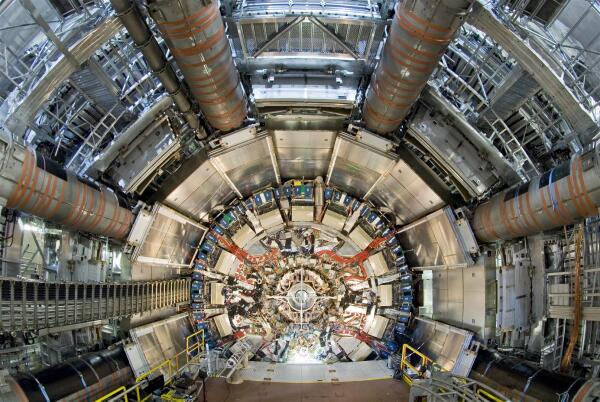

For CERN, there is no better time to form a charitable foundation, says Matteo Castoldi, head of its development office. CERN’s Large Hadron Collider, and the discovery of the Higgs boson, has “captured the public imagination” as much as the Apollo missions did in the 1960s, he says. The organization is already taking advantage of this, “but there is much more we could do, and that’s where the foundation comes in”.

Registered in Switzerland last month, the CERN & Society foundation is designed to put CERN’s fund-raising efforts on a firmer footing: although the lab has accepted donations in the past, charitable status means that donors can now pledge tax-deductible gifts. Organizers hope that this will encourage more — and larger — donations.

CERN director-general Rolf-Dieter Heuer stresses that such funding will not replace the institute’s core budget, paid for by member states. Instead, the proceeds are aimed at activities that this funding cannot stretch to: school projects, the development of medical spin-offs such as proton therapy (the use of proton beams to kill cancer cells), and meeting the huge demand for general-interest and science-related visits. But if a donor has an explicit desire for their gift to go towards research, CERN would consider this, adds Heuer.

Continental Europe has been slow to embrace professional fund-raising and a wider culture of philanthropy: it lags behind the United Kingdom by about 20 years and the United States by 50 years, says Johannes Ruzicka, managing director of the fund-raising consultancy Brakeley in Munich, Germany, which is advising EMBL. More research institutions are thinking about this kind of fund-raising, he adds, but few actually make the leap, owing to the significant investment and administrative hassle that goes with setting up a foundation.

European universities have been bolder than research institutions, and have been trying to emulate the fund-raising abilities of their US counterparts for some time, says Kate Hunter, executive director of Europe’s arm of the Council for Advancement and Support of Education, based in London. “There’s been a massive trend over the last decade to reinforce that universities are charitable entities in their own right, and that they are a legitimate cause to support,” she says. “So I do think it’s an interesting development if pure science research institutions see that they can do that too.”

There are reasons for the reticence of institutions. Some facilities that are funded by several countries fear that raising large amounts of money through philanthropy could encourage governments to cut their contributions, says Ruzicka. But others believe that state-funding agreements have a finite lifespan and so need to be backed up by other funding sources, he adds.

ITER’s goal — to build an experimental fusion reactor that will serve as a stepping stone towards harnessing effectively limitless energy — already makes it an attractive candidate for philanthropists. The facility is creating its charity framework directly in response to people asking to contribute, says an ITER spokeswoman. The cash will go towards educational activities, internships, exhibitions and conference travel costs, although ITER is not yet authorized to accept tax-deductible donations.

CERN has no history of professional fund-raising, and Castoldi acknowledges that progress will be slow. It also remains to be seen to what extent particle physics will appeal to philanthropists. Hunter is optimistic. “Places like CERN and other research institutions are doing amazing things that will ultimately deliver public benefit, so if those organizations can make that case, that can be quite attractive for donors,” she says.

Heuer says that CERN is “completely open” to offers of any size, and Castoldi hopes that it will raise 25 million Swiss francs ($28 million) in the next five years. Individuals, trusts and companies can donate, and contributors will be recognized in various ways.

Those who make substantial gifts could even have a facility at CERN named after them, says Heuer — but not, he adds, any particles the laboratory might discover. “That is science,” he says. “We don’t touch that.”

This article is reproduced with permission and was first published on July 15, 2014.